Much is said about Islamisation, but far less about the phenomenon that in reality constitutes its most effective form: entrism. The word comes from political science and refers to the strategic infiltration of a society’s institutions – from within and from below – with the aim of transforming them in a particular ideological direction.

Where the terrorist seeks to break the system through violence, entrism seeks to dissolve it quietly – through declarations of loyalty, appointments, committee seats, and political alliances. It requires no bombs, only patience, positions, and the right vocabulary of “inclusion” and “diversity.”

Entrism is therefore the slow but far more dangerous form of jihad.

Shifts of Power

When a Muslim police officer – such as Elvir Abaz from Funen Police – uses his position to monitor, pursue, and register political opponents, not least Islam critics like Naser Khader and Halime Ogüz, it is not merely a personal failure or an abuse of office. It is a sign that Islamist thinking has gained a foothold precisely where citizens should be able to trust most in neutrality and equality before the law.

When a researcher like Sameh Egyptson – who in his PhD documented how political Islam infiltrates Swedish society – is met with accusations of academic misconduct, it is not only a question of scholarly ethics. It is because the very act of analysing entrism triggers its reflex: the system’s immune response turns not against the problem, but against the critic.

England – A Warning from the Future

To understand the consequences of entrism, one need only look to England. Over decades, a combination of moral confusion and fear of offence has turned the country into a textbook example of how Islamic power and norms can move into the core institutions of the state and society.

The Pakistani grooming gangs that in towns like Rotherham, Telford and Rochdale raped and abused thousands of young girls were for years protected by the silence of the authorities. The police, social services, and media feared accusations of racism more than they feared the injustice done to the victims. That is entrism in practice: a system paralysed by its own tolerance.

Today we see Muslim mayors in the largest English cities – including Sadiq Khan in London – who consistently place identity politics and “inclusion” above social cohesion and freedom of speech. Meanwhile, knife crime is exploding, and public trust in the police is collapsing.

When Israeli football fans are banned from attending a match in Birmingham “for their own safety,” while pro-Palestinian demonstrators are allowed to dominate the streets unhindered, it shows how the balance of power has shifted. Those who threaten are rewarded; those who are threatened are restricted.

The result is cultural and institutional capitulation: a police force that paints rainbows on patrol cars while assaults go unsolved; a university system where criticism of Islam is marginalised; and a public sphere where freedom of expression is no longer a principle but a bargaining chip.

If We Continue to Look Away

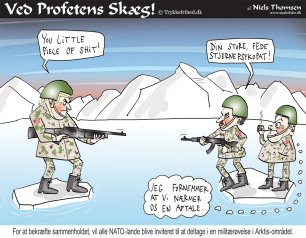

Denmark is not there yet – but we are on our way. And if politicians continue to close their eyes, entrism will likewise transform our institutions. Public authorities will become more concerned with avoiding “offence” than with defending free speech. The police will lose public trust. Academia will be purged of voices that challenge Islam.

Entrism is not a theory. It is a fact – documented in Sweden, visible in England, and quietly advancing in Denmark.

That is why we must ask the uncomfortable questions now:

How do we prevent political Islam from gaining a foothold in our institutions?

And do we, as a society, have the courage to say that democracy is not obliged to commit suicide in the name of tolerance?